2024

Safeher - Feel Safe, Wherever You Go

Year 2024

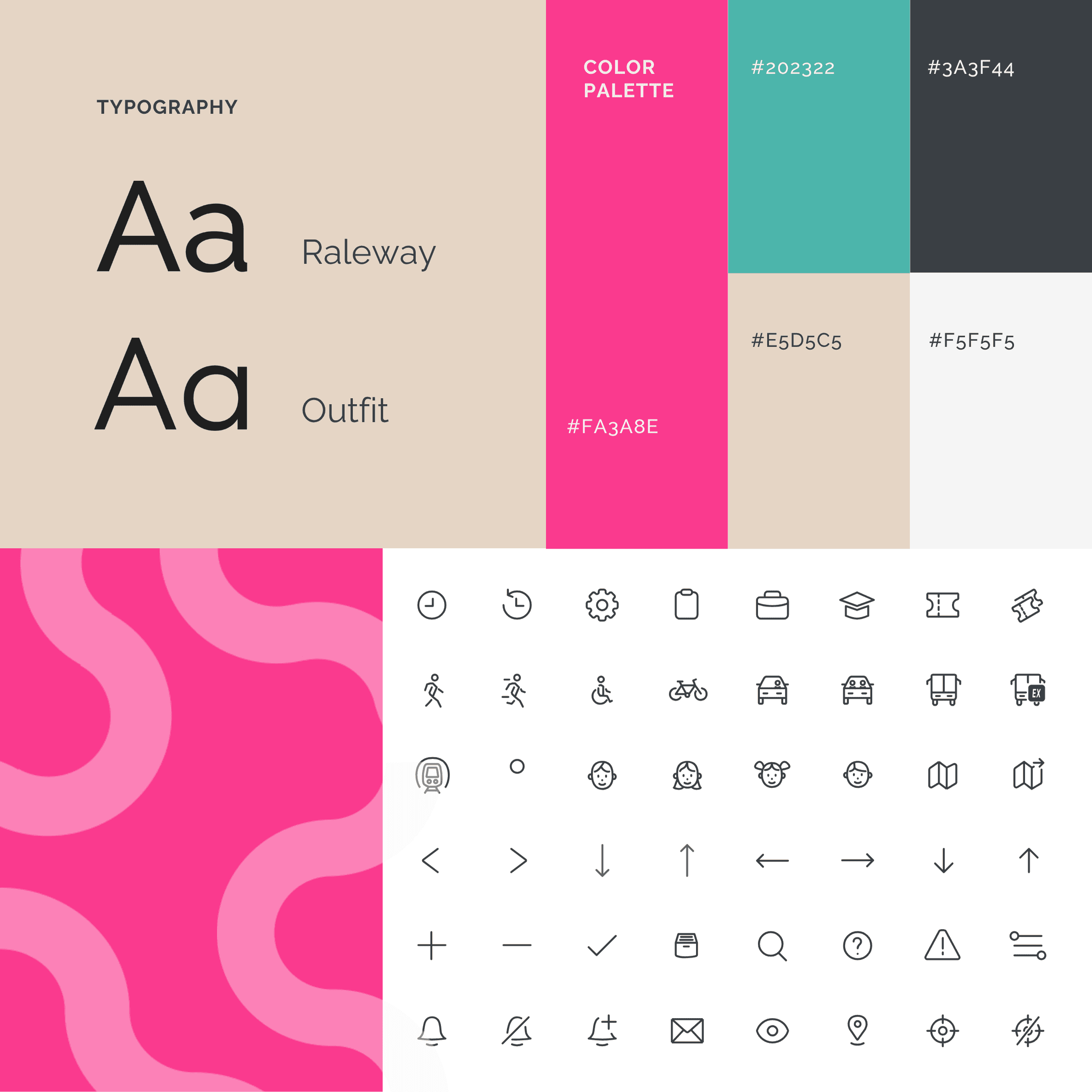

Service Design

Expereince Design

Design System

I’ve felt uncomfortable and even harassed at times. It happens quite often on buses, sadly.

[Empathize]

My thesis began with something I know too well — the experience of commuting as a woman in Karachi. I’ve spent over 5 years using rickshaws, buses, and ride-hailing apps just to get to class. That commute was never simple. It was exhausting, unpredictable, and sometimes unsafe.

I wasn’t alone. Through conversations with dozens of women, I started to uncover the same fears I had:

[User Persona]

I do prefer the rickshaw over a car because it’s open, and I feel like I can jump out easily if something happens.

I usually plan and head to the bus station at least an hour and half in order to find a bus and reach just in time for my classes

These weren’t just inconveniences. They were real safety risks — ones that shaped how women moved, worked, and lived.

Commute is a wicked problem.

[Define]

Commute was a complex, messy problem — trying to solve it for everyone meant solving it for no one. I had to zoom in, focus, and design for one group deeply enough to make a real impact.

[Define]

The insight was clear:

“Waiting” is the most vulnerable point in the entire commute.

Poor lighting, long waits, overcrowded stops, and lack of visibility all combine to create an unsafe, unprotected space — especially after sunset.

According to PIDE and IIPS reports,

not because of the commute itself, but because of the waiting around it.

Waiting didn’t feel neutral. It felt dangerous.

That’s where the problem — and opportunity — truly lived.

[Problem Statement]

[Target Audience]

Women

18 - 35 years old

Student or Working

Karachi, Pakistan

Primary Modes of Transport: People’s Bus Service, Karachi Breeze (Green Line, Orange Line), rickshaws and ride-hailing services

I wanted to fix everything,

Because it felt that personal.

[Ideate]

I explored how design could transform the waiting experience from a vulnerable pause into a secure, visible, and supportive moment.

From fieldwork, I identified both functional and emotional needs:

Because for me, this wasn’t just a design thesis — it was years of living through the problem. I wanted to build everything at once.

My early concepts tried to tackle every layer of it

But the problem wasn’t about features. It was about foundations.

[Test]

User testing made one thing painfully clear:

I was designing for a system that

barely existed.

Over 150 women interacted with my early concepts — kiosks, color-coded maps, ride integrations. But the feedback I got wasn’t about what I had designed. It was about what wasn’t there at all.

[Test]

This wasn’t just about comfort — it was about safety, about presence, about being seen in a system that often forgets its most vulnerable commuters.

That’s when I realized: no kiosk, app, or screen would matter unless the physical space — the very act of waiting — felt safe.

So I went back to square one.

Not to simplify the idea,

but to get closer to the need.

From scattered ideas to a real,

layered system.

[Design]

Once I grounded the problem in reality, I focused on designing what women truly needed:

Once I grounded the problem in reality, I focused on designing what women truly needed:

Not just a screen, but an ecosystem — space, tools, and trust — all working together.

[Design]

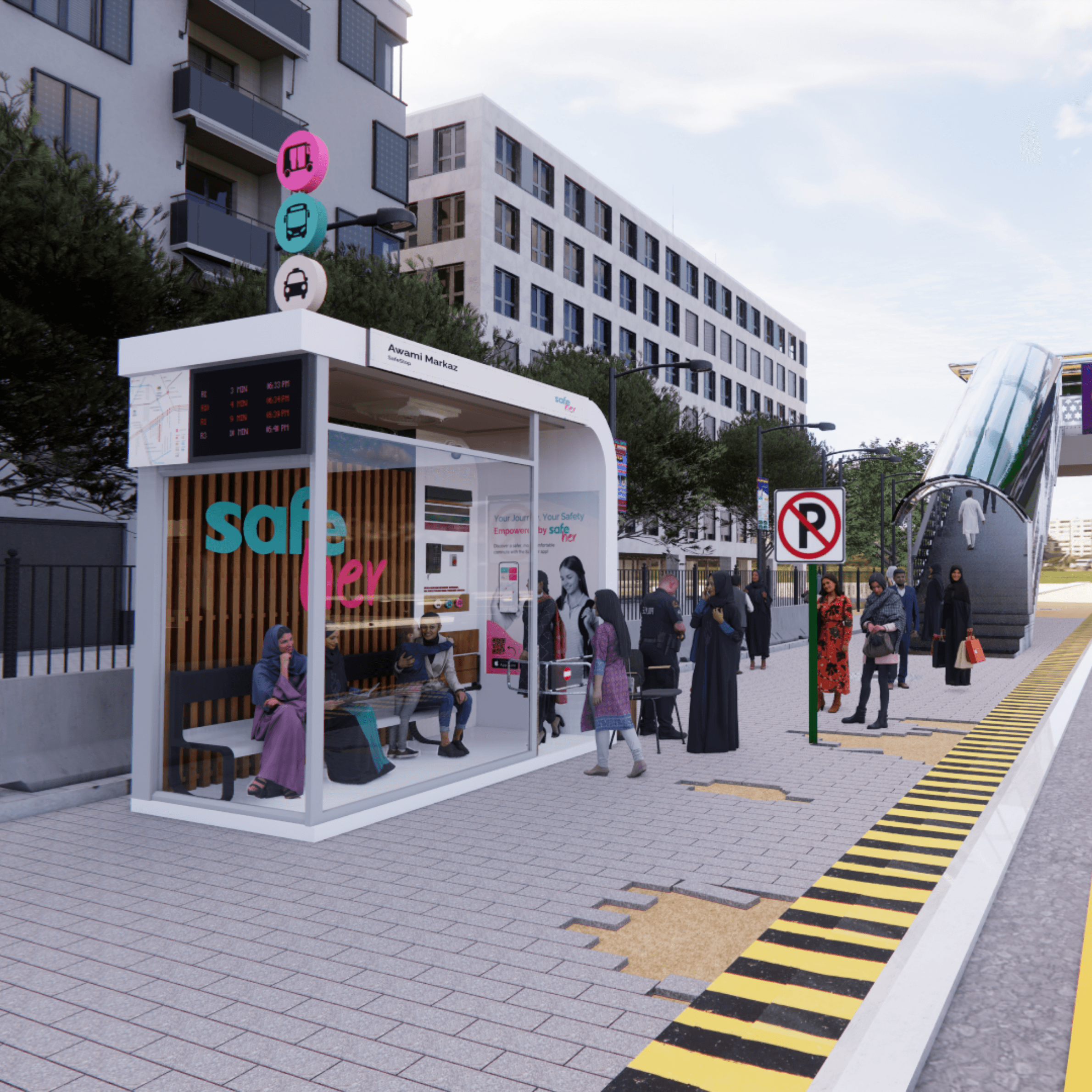

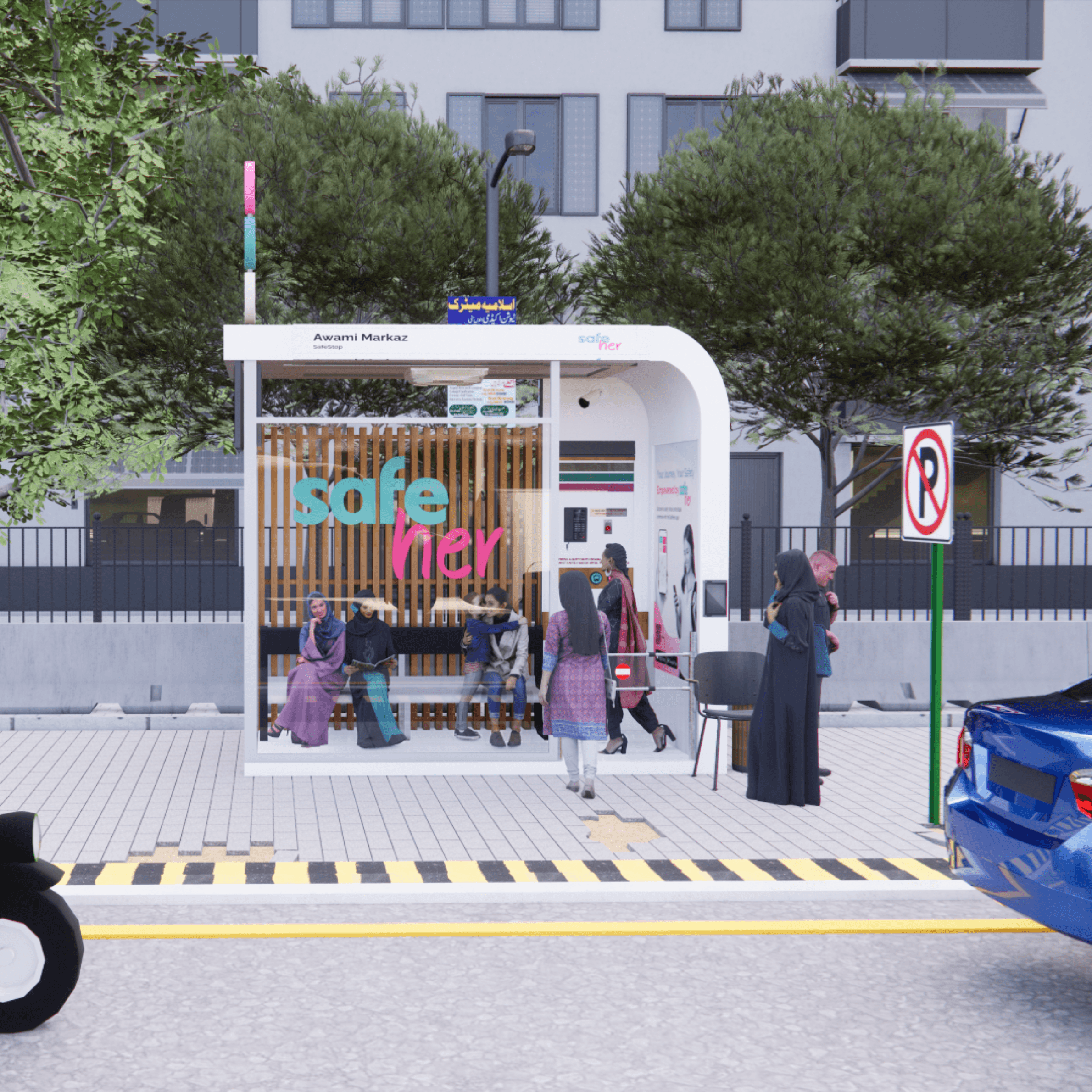

The SafeStop stations were designed to make waiting safer, more predictable, and less isolating.

Instead of futuristic features, the design focused on:

[Design]

The SafeStop stations were designed to make waiting safer, more predictable, and less isolating.

Instead of futuristic features, the design focused on: